My final stop on mainland Europe was a two-night stay with Hilde and Dirk in Ypres located in the Province of West Flanders, Belgium. The actual official spelling of the town is Ieper, the Dutch version, but Ypres the French version is most commonly used by English speakers. During WWI, English-speaking soldiers and Winston Churchill often referred to Ieper/Ypres by the deliberate mispronunciation "Wipers". During WWI, British soldiers even published a wartime newspaper called The Wipers Times.

No town in the world has a stronger connection with WWI and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). It is not too much of an exaggeration to say, within a short walking distance in any direction from the Ypres town centre, you will find a CWGC WWI cemetery or memorial that is waiting to be discovered. No matter where you turn and or walk, you will find somewhere to pause, reflect and remember the horrific events of The Great War.

|

| A google map of Ypres and the surrounding area, showing the WWI CWGC Cemeteries |

WWI historical information about Ypres ~

The town lay at the heart of one of the most notorious battlefields of the Western Front. The Battles of Ypres were a series of engagements during WWI between the German and the allied armies ~ Belgian, French, British, the Canadian Expeditionary Forces, Australians and New Zealanders. Ypres occupied a strategic position during the war because it stood in the path of Germany's planned sweep across the rest of Belgium and into France from the north, known as the Schlieffen Plan.

Belgium’s neutrality

established by the 1839 First Treaty of London, was guaranteed by Britain and

therefore with Germany's invasion, it brought the British Empire into the conflict.

At the beginning of the war, the German army surrounded the town on three

sides, bombarding it throughout much of the next four years. In order to counter attack,

British and allied forces made costly advances from the Ypres Salient into the

German lines on the surrounding hills.

The Salient

was formed during the First Battle of Ypres in October and November 1914, when

a small British Expeditionary Force succeeded in securing the town before the

onset of winter, pushing the German forces back to the Passchendaele Ridge. The

Second Battle of Ypres began in April 1915 when the Germans released poison gas

into the allied lines north of Ypres. This was the first time gas had been used

by either side, the violence of the attack forced an allied withdrawal and a

shortening of the line of defence.

There was

little more significant activity on this front until 1917 during the Third

Battle of Ypres, when an offensive mounted by Commonwealth forces to divert

German attention from a weakened French front further south. The initial

attempt in June to dislodge the Germans from the Messines Ridge was a complete

success, but the main assault north-eastward, which began at the end of July,

quickly became a dogged struggle against determined opposition and the rapidly

deteriorating weather. The campaign finally came to a close in November with

the capture of Passchendaele.

A German offensive of March 1918 met with some initial success, but was eventually checked and repulsed in a combined effort by the allies in September. During the all engagements, Commonwealth casualties are estimated to have surpassed one million.

During the course of the war the town was all but obliterated by

the artillery fire. From the pictures below you can see the devastation left by

the brutality of the war on the town.

During the

four years of the war, the entire town centre was totally destroyed. Yet just

ten years after the Armistice of November 1918, Ypres looked like the town had

never experienced any war related devastation, almost all the destroyed buildings had been

rebuilt.

Today Ypres

is generally considered one of the best examples of post-conflict

reconstruction. In a similar way to my first visit during April 2000, I found

the town to be a joy to walk around, with its magnificent Cloth Hall to its

historic Grote Markt marketplace and outdoor cafés. The town is packed with

historical buildings and curios that tell its millennia-long history, but for

me the most impressive and encouraging feature of Ypres which seems to be

embedded deep within the towns deep culture, is the need to remember and forever

retain the memory of those who fought and died there during WWI.

Ypres now ....

|

| This is where I stayed on my last visit to Ypres in April 2000 |

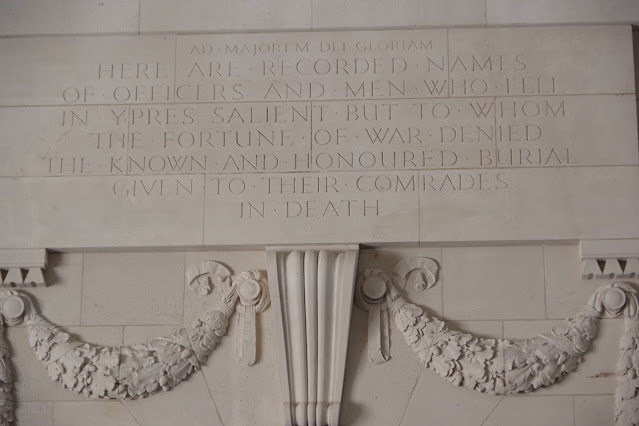

Within

Ypres is the very impressive Menin Gate. It is one of four memorials to the

missing in Belgian Flanders, which covers the area known as the Ypres Salient. The

battles of the Salient claimed many lives on both sides and after the war, it

quickly became clear that a means of commemoration to the Commonwealth forces

with no known grave would have to be divided between several different sites.

The site of

the Menin Gate was chosen because of the hundreds of thousands of men who

passed through it on their way to the battlefields. It commemorates casualties

from the forces of Australia, Canada, India, South Africa and United Kingdom (in

the case of the UK only those killed prior to 16 August 1917) who died in the

Salient. United Kingdom casualties who died after 16 August 1916 and all New

Zealanders with have no known grave, are named on the memorial at Tyne Cot, a

site which marks the furthest point reached by Commonwealth forces in Belgium

until nearly the end of the war. New Zealand casualties who died prior to 16

August 1917 are commemorated on memorials at Buttes New British Cemetery and

Messines Ridge British Cemetery.

The Menin Gate memorial now bears the names of 54583 officers and men whose graves are not known. The memorial, designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield with sculptures by Sir William Reid-Dick, was unveiled by former Field Marshall Lord Plumer on 24 July 1927. The following is part of his speech during the unveiling ceremony, which attempted to give comfort to the parents and relatives of the missing soldiers of the Ypres battle fields ~

“... One

of the most tragic features of the Great War was the number of casualties

reported as 'Missing, believed killed'. To their relatives there must have been

added to their grief a tinge of bitterness and a feeling that everything

possible had not been done to recover their loved ones' bodies and give them

reverent burial. That feeling no longer exists; it ceased to exist when the

conditions under which the fighting was being carried out were realized.

But when

peace came and the last ray of hope had been extinguished the void seemed

deeper and the outlook more forlorn for those who had no grave to visit, no

place where they could lay tokens of loving remembrance. ... It was resolved

that here at Ypres, where so many of the 'Missing' are known to have fallen,

there should be erected a memorial worthy of them which should give expression

to the nation's gratitude for their sacrifice and its sympathy with those who

mourned them. A memorial has been erected which, in its simple grandeur,

fulfils this object, and now it can be said of each one in whose honour we are

assembled here today:

‘He is

not missing; he is here’.”

The Menin Gate Last Post ceremony ~

Following

the opening of the Menin Gate Memorial in 1927, the citizens of Ypres wanted to

express their gratitude towards those who had given their lives for Belgium's

freedom. To achieve this, every evening at 8.00pm, buglers from the Last Post

Association close the road which passes under the memorial and sound the

"Last Post". Except for the occupation by the Germans during WWII,

when the daily ceremony was conducted at Brookwood Military Cemetery in Surrey,

England, this ceremony has been carried on uninterrupted since 2 July 1928. On

the evening of 6 September 1944 when Polish forces liberated Ypres during WWII,

the ceremony was resumed at the Menin Gate despite the fact that heavy fighting

was still taking place in other parts of the town.

I would like

to share my experience of the Menin Gate Last Post ceremony during my last

visit to Ypres on 9 April, 2000. I was with my parents and Ypres was the last

stop on our four-day war grave visit to Belgium and The Somme in France. I

remember it was a cold, damp and overcast evening, which for me did not dull my

enthusiasm for the wonderful culture and history of Ypres.

We were at

the Menin Gate well before the 8.00pm Last Post, which gave us the opportunity to

walk around the memorial, to view closeup the magnificence of the structure with

its hundreds of internal and external panels, filled with the 54583 names of WWI

military officers and men from the Commonwealth, who paid the ultimate price at

the Ypres Salient and have no known grave. Shortly before 8.00pm, the local

police closed off the road at both ends which passes under the gate. I would

say at this point there were about a dozen or so in attendance, like us they

looked like tourists visiting the town.

Before the

ceremony started, I raised my mid-1990’s era over-sized video camera to my eye

and began recording. I recorded the smartly uniformed buglers marching out in

step, before standing to attention in the middle of the roadway. After a pause they

played the Last Post, which was then followed by a two-minute silence. I

continued to record as the buglers left and the police reopened the road. At

this point after what was probably six or seven minutes of recording, I lowered

the camera and could not believe the sight before me, there were perhaps a

couple of hundred people who had arrived during the short time I had been recording.

But what was truly amazing, I would say a large number of them were locals who had come out from their nearby homes ~ I will never forget that. As I looked around

at the faces, many in the crowd were wiping away tears. My immediate thought was ~ “and this

happens every night” ~ that is dedication, that is remembrance, that is Ypres.

Always at the end of the nightly Last Post ceremony the crowds will melt away in muted contemplation, while the names of the missing remain. The buglers will be back tomorrow and the day after, and the day after that. It is a remarkable tribute by the people of Ypres to those who died fighting for their freedom ~ truly an unforgettable experience.

This evenings Last Post Ceremony ...

Unfortunately,

during this visit, the Menin Gate was partly closed for restoration work which began

in April 2023. Built in the 1920’s, the gate has been exposed to the weather

and pollution throughout its life and has required constant maintenance and

care. To guarantee its long-term preservation, funding from the CWGC along with

premiums from Flemish Government and the Town of Ypres, a two-year full-scale

restoration of the memorial is being undertaken. As you seen from my photos, the

Last Post ceremony continues nightly at the gate.

The Menin Gate under restoration ...

A short drive from Ypres is Passchendaele, the location of the Third Battle of Ypres which began on 31 July 1917. Over the following 103 days of fighting in this part of Belgian Flanders, hundreds of thousands of soldiers on both sides would die. I cannot begin to imagine what these men went through, but photographs easily available on the internet may begin provide a unique window into their harsh world of mud, shell holes, barbed wire and death or the words written in January 1918 by R. A Colwell may help ~

“There was not a sign of life of any sort. Not a tree, save

for a few dead stumps which looked strange in the moonlight. Not a bird, not

even a rat or a blade of grass. Nature was as dead as those Canadians whose

bodies remained where they had fallen the previous autumn. Death was written

large everywhere.”

In addition

to the many memorials within the surrounding area to those with no known grave,

there is also more than two dozen cemeteries with the graves of those who died

in and around Ypres. Of those Tyne Cot is the biggest, in fact it is the largest CWGC cemetery in the world and no visit to this area would be complete

without experiencing this location. Within the perimeter wall there are 11961

Commonwealth servicemen buried or commemorated, 8373 (70%) of the burials are

unidentified ~ “Known Unto God”. There are special memorials to more than 80

casualties known or believed to be buried among them. Other special memorials

commemorate 20 casualties whose graves were destroyed by shell fire, there are also 4

German burials, of which 3 remain unidentified.

The Tyne Cot Memorial which forms the north-eastern boundary of the cemetery, commemorates nearly 35000 servicemen from the United Kingdom and New Zealand who died in the Ypres Salient after 16 August 1917 and whose graves are not known. At the front of the cemetery are the graves of South African soldiers whose remains were discovered only a few years ago. The distinctive rising sun of the Australian Imperial Force’s badge is inscribed on many gravestones. At the heart of the cemetery is one of three German concrete pillboxes or blockhouse whose capture cost the lives of so many. The Cross of Sacrifice was built on top of one, reportedly at the suggestion of King George V.

|

| German concrete pillbox then ... |

|

| German concrete pillbox now ... |

Tyne Cot Cemetery ~

Before

I left Tyne Cot, I took one last look across the nearly 12000 graves, of which 8373

are identified as ~ Known Unto God. I wondered if visitors to the cemetery ever

stop and pause at those graves. The fortunate ones who are identified, will have

their names, nationalities, regiments, age, date of death and possibly a

personal inscription for visitors to read and dwell upon, but the unknowns have

nothing. It breaks my heart to think of this, they too had loved ones who missed

them and who loved them. The following poem written by Cyril W. Crain, a British

soldier who landed in Normandy on 6 June 1944, is the perfect reminder to those

who plan visit a CWGC cemetery.

The Forgotten One

Why does no one pause at my grave?

After all, I too was brave.

They pass me by and kneel and pray

At a nearby grave or across the way.

I also fought for what was right,

And here I lie by day and night.

Is there a reason they pass me by?

If there is, please tell me why.

I turned away with puzzled mind,

The answer to his words to find.

Then I looked upon the stone,

A gallant soldier, name unknown.

So, remember, if you pass his way,

Pause awhile to chat and pray

While

in Ypres, I took a short walk from the town centre to Ramparts (Lille

Gate) Cemetery, which is one of many within the same walking distance.

The

cemetery grounds were assigned to the United Kingdom in perpetuity by King

Albert I of Belgium in recognition of the sacrifices made by the British Empire

in the defence and liberation of Belgium during the war.

The

cemetery is located by the towns Lille Gate, on top of the old rampart, over

what had been dug-outs. It was begun by French troops in November 1914 and used

by Commonwealth units at intervals from February 1915 to April 1918. The

cemetery designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield, who was also responsible for the

nearby Menin Gate memorial, contains 198 Commonwealth burials of the First

World War, the French graves have been removed.

The poem "Ypres" written by Robert Laurence Binyon, who served with the Red Cross during WWI and witnessed for himself the devastation and death, depicts the devastation of Ypres during WWI. It begins with a sense of pride and remembrance of Ypres' former glory, with its towers and trees. However, the following stanzas starkly contrast this idyllic image with the shattered ruins and bones that now lie beneath.

The poem's tone is somber and evocative, capturing the

horror and tragedy of war. It personifies the dead soldiers as an army

"that is biding," awaiting a call to fight once more. This creates a

sense of eerie anticipation and the supernatural, as if the dead themselves are

ready to rise up and seek vengeance.

The poem ends with a resounding call to action, urging the

living to listen for the bugle's call and to join the dead in fighting for the

cause. It emphasizes the indomitable spirit and sacrifice of those who have

fallen, and serves as a poignant reminder of the cost of war.

Ypres

On the road to Ypres, on the long road,

Marching strong,

We'll sing a song of Ypres, of her glory

And her wrong.

Proud rose her towers in the old time,

Long ago.

Trees stood on her ramparts, and the water

Lay below.

Shattered are the towers into potsherds--

Jumbled stones.

Underneath the ashes that were rafters

Whiten bones.

Blood is in the cellar where the wine was,

On the floor.

Rats run on the pavement where the wives met

At the door.

But in Ypres there's an army that is biding,

Seen of none.

You'd never hear their tramp nor see their shadow

In the sun.

Thousands of the dead men there are waiting

Through the night,

Waiting for a bugle in the cold dawn

Blown for fight.

Listen when the bugle's calling Forward!

They'll be found,

Dead men, risen in battalions

From underground,

Charging with us home, and through the foemen

Driving fear

Swifter than the madness in a madman,

As they hear

Dead men ring the bells of Ypres

For a sign,

Hear the bells and fear them in the Hunland

Over Rhine!

Below are related CWGC to the places I have visited during my two days in Ypres, click on the images or links below ~

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RTdLBFoFJyw&t=115s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5BJbNTvclU4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ftcdQuXRSjs

No comments:

Post a Comment