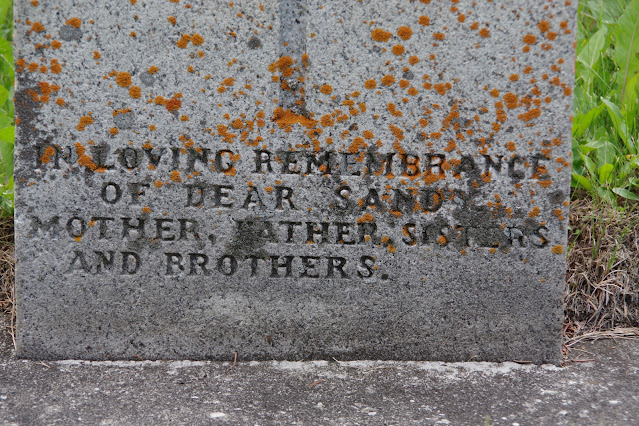

The grave of a young Scotsman, Lance Corporal Alexander “Sandy” Collie of The Lovat Scouts, Service Number 326148.

Died 20th January 1944 aged 23.

Son of William and Grace Dolina Collie, of Aviemore, Inverness-shire, Scotland.

Buried ~ Jasper Municipal Cemetery, Jasper, Alberta, Canada

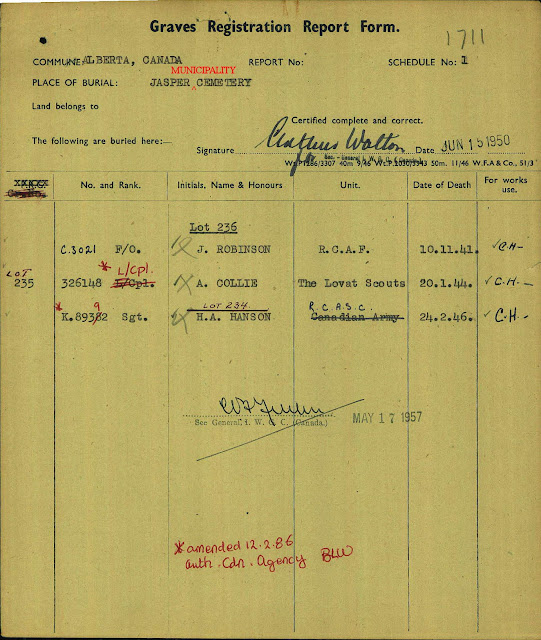

Other CWGC graves in this cemetery ~

Flying Officer James Robinson, RCAF, Service Number: C/3201.

Died 10th November 1941 aged 44

Son of Herbert and Jane Robinson, of Carrot Creek; husband

of Mildred J. Robinson, of Jasper.

Sergeant Henry Andri Hanson, Royal Canadian Army Service

Corps, Service Number: K/89392.

Died 24th February 1946 aged 41

Husband of Mary Edna Hanson, of Jasper.

CWGC ~ Grave Registration Report Form for Jasper Municipal Cemetery ...

The Lovat Scouts and their Jasper experience ~

Rated them

Rated as one of the toughest units in the British Army during the Second World War, the Lovat Scouts were sent to the Rocky Mountain resort town of Jasper in 1944 to train as a mountain warfare elite. The British had found themselves out fought in Norway and Greece by the Axis mountain warfare specialists and were determined to redress the balance. So, when Britain’s wartime leader Winston Churchill decided he needed a unit specializing in mountain warfare, the Lovat Scouts were an obvious choice.

The regiment had been originally raised by Lord Lovat during

the Boer War in 1899. The regular troops of the British army were struggling to

beat the sharp-shooting, hard-riding, farmers of the Orange Free State and the

Transvaal in South Africa. So, Lord Lovat raised a regiment of sharpshooters

from the private game wardens and hunting guides from his own and his Neighbours' Highland estates. Many of the officers were local landowners.

At the start of the Second World War, they were sent to garrison the Faroe Islands, half-way between Shetland and Iceland. In 1942 the Lovat Scouts returned to Britain to become the reconnaissance regiment of the 52nd Lowland Division. Churchill already had his eye on the unit for special work and at one point considered sending them to the Middle East as commandos. The 52nd Division was earmarked for a mountain warfare role and this meant specialist training for the Lovat Scouts.

In 1943 they started intensive training in the Cairngorm

Mountains of Scotland before heading off to Wales for rock climbing instruction

at the Commando School of Mountain Warfare. After the training in Wales was

completed, the regiment was sent to the Canadian Rockies for even more

instruction in mountain warfare.

On the night of January 6, 1944 after crossing the Atlantic,

the Lovat Scouts caught sight of the sparkling lights of the legendary New York

skyline – unlike Britain, there was no black-out in the United States. It had

been a long dry trip, the White Star Line, owners of the troopship Mauretania,

had banned alcohol on board.

But one lucky piper, a man from the remote island of Uist,

somehow managed to fill his pockets with bottles of whisky somewhere between

the ship’s gangplank and the train to Jasper. The 2500-mile journey from New

York to Jasper in the Rockies on two special trains took three days.

They arrived to find the tiny mountain resort in the grip of

winter. Temperatures were typically arctic and several soldiers suffered frost

bite on their march from the train to their quarters a few miles out of town at

Jasper Lodge.

The 600 men were issued with U.S. arctic clothing, including fur-trimmed parkas, down-filled sleeping bags, and rubber-soled boots. The man in charge of putting the training program together, Wing Commander Frank Smythe, must have envied the Highlanders their boots. He got to within one thousand feet of the top of Mount Everest in 1933, and might well have been the first man to reach the summit, if he had been wearing the U.S. boots instead of British hobnail soles.

The rigorous training soon took its toll. It had been

planned to use the local golf course to train the men how to ski. But a lack of

snow at lower altitudes meant many of the Highlanders were forced to graduate

to the nearby mountain slopes before they were ready. Within a short time 30

men had broken arms and legs or were suffering from serious sprains. A 50-bed hospital had been set up in Jasper to deal with just such fall-related training

injuries. Frostbite and snow blindness were major concerns, some men were

slower than others to realize that while the sun might be bright in the sky, a

temperature of –20C would freeze exposed skin in seconds.

Major Sir John Brook only survived an avalanche by “swimming” through the crashing flood of snow. Lance Corporal Sandy Collie, a sturdy well-liked man from Upper Tullochgrue, Aviemore, was not so lucky. While part of training party tackling Nigel Peak on January 20th, he was caught in an avalanche along with Corporal Angus Cameron. One of Cameron’s gloves was seen sticking out of the snow after the avalanche had passed and he was quickly dug out. It was Cameron who located Collie’s body about five feet under the snow an hour later. All attempts to revive Collie failed and he was buried in the little cemetery outside town four days later.

The regiment finally saw action in Italy. But not with the

52nd Division, which had been sent to France after D-Day. Instead, the regiment

was attached to the 10th Indian Division, which used them either as ordinary

infantry or for patrols behind German lines in the hilly country of the

Apennines. The training they had done in Jasper to prepare for high altitude

mountain warfare was rarely put into practice.

No comments:

Post a Comment