Even my dad’s own personal wartime experiences did not make the war any more real to me. His family home in Knightswood,

My dad then went on to say that it had always been his wish and deep desire to make a visit to Hugh’s grave in

From information I had read prior to our visit to

|

| Letter from the War Office dated 4 June 1946, informing Hugh's late father of his temporary grave "at De Meir 5 3/4miles east southeast of Brecht, Belgium." |

|

| Letter from the War Office dated 3 July 1946 informing Hugh's late father of his permanent grave "in Lepoldsburg (Bourg Leopold) British Cemetery, 20 miles southwest of Turnhout, Belgium. Polt V, Row A, Grave No.12" |

|

|

Photo of temporary grave marker received in a letter to Hugh’s mother from the War Office dated 21 May 1948. |

|

| The grave of Private David Sprott of The Kings Own Scottish Borderers at Leopoldsburg War Cemetery Inscription ~ A LITTLE CORNER OF A FOREIGN LAND THAT IS FOREVER SCOTLAND |

I remember in late 1999 while the planning the trip to

From

During our journey through

After my return to

After a process of applications via the British Ministry of Defense, I fortunate to receive Hugh's military records. From those I learned the following in summary form ~

Member Mrs. Millicent Booth, widow of Eddie Booth, RE, phoned me this morning. It seems that Eddie knew Hugh very well and Millicent would love to contact you and pass on everything she knows.

As if that wasn't pretty good news, it suddenly got even better. My editor's cap glowed and my pen shook when she told me she is in possession of a leather "Military Housewife" embossed with Hugh's name and details! I can already see the article in June’s PBN.

Kind regards,

Almost immediately I called Hugh’s sister Jean who still lived at 599 Duke Street, the original home of her grandparents, the location of her parents’ marriage in January 1917 and where both she in 1920 and Hugh in 1917 were born. Jean’s reaction to this update was similar to my own; she was absolutely thrilled and excited. She also clearly remembered the existence of Hugh’s Military Housewife and was delighted about its rediscovery after so many years.

Of the three friends only Eddie, Serial No. 2067466 was fortunate to survive the war. George, Serial No.1916609 was killed on 20 August 1944 aged 28 and is buried at Banneville-La-Campagne War Cemetery, France. From the CWGC web-site, I found that he was the son of Samuel and Helene Rumph and husband to Beatrice (nee ~ Beatrice R. Staab).

“On the 20th of August we had our first casualty. George Rumph took the Col. in his Jeep to a bridging site. They had been at the site for a while when the

|

| The grave of George Sidney Rumph at Inscription ~ A LOVE THAT CANNOT DIE IS

WITH THEE IN THY REST IN THE HOME BEYOND THE SKY |

“……..After the excitement with the Yanks we returned to the unit, only to find that in our absence some Royal Army Service Corps (RASC) blokes had parked five three-ton lorries nose to tail in the lane. They had not bothered to camouflage them at all. A jerry tank had arrived on the scene, spotted the five lorries, put a shell in the first lorry and one in the rear lorry, then hit the three in the centre. He must have spotted our two vehicles and put a shell in the engine compartment. Unfortunately, Jock had taken cover under the engine and was killed instantly. The powers that be decided that we were in the wrong position and we had to move. This meant that we had to leave Jock behind. His body was collected by burial squads and is now interred in

Throughout all my research into Hugh, I have been fortunate to come in contact with various sources of information, one of those is author and historian Guido Van Wassenhove. Guido has written a book “Wuustwezel and Loenhout in World War Two” (Wuustwezel en Loenhout in de tweede wereldoorlog)” describing the war activities in his home town of

“…………The name of Lance Corporal Hugh Wright did arouse my interest.

A German Panzer (Jagdpanther) had crossed the British lines. The Jagdpanther drove along Baan (coming from the direction of the

On its way he shot three grenades at the church tower where three men of the Signals observed the area, especially the area of Stone Bridge (the road from Wuustwezel towards Loenhout) to direct the division artillery. The third shot from the tank killed them all.

This account is similarly described on page 192 of the book “The Polar Bears Monty’s Left Flank” by Patrick Delaforce.

|

|

Wuustwezel ~ The Polar Bear monument is

at location 1 Hugh was killed at the location marked 2 |

|

|

“Where the car turns into the street is the location where Hugh was killed” |

|

|

“From this location the German Jagdpanther shot at

the trucks at the end of the street” |

Frederick Sidney Houghton, Serial No. 2146504 the other Royal Engineer killed at the same time as Hugh was aged 24 and came from Sunderland, County of Durham. He was the son of Frederick Percy and Louie Houghton, husband to Jean and father to Brian Frederick Houghton who at the time was aged just two months. Like Hugh, Frederick was also buried in

|

Frederick Sidney

Houghton's grave at Leopoldsburg War Cemetery, Limburg, Belgium Inscription ~ DEARLY LOVED SON OF FREDERICK AND LOUIE HOUGHTON AND HUSBAND OF JEAN "TILL WE MEET

AGAIN" |

|

Here the German counter attack was halted 21~22 October 1944 by The 49 West Riding Infantry Division Wuustwezel to our

liberators 21 October 1984 |

After Hugh’s death Eddie Booth managed to recover his Military Housewife. Made from fine soft leather the housewife incorporates the Royal Engineer crest embossed in full colour on the front. Penned below the crest is Hugh’s hand written name and service number. The contents of the housewife remain as they were at the time of his death. Those include a number of sewing needles, thread, spare buttons, safety pins and a length of cotton ribbon. Hugh’s sister Jean told me that the housewife was given to him as a present by his girlfriend Jessie Stevenson.

It was with much fulfillment and gratification for Millicent that she would finally complete Eddie’s decades long desire and wish, to return the unique memento of Hugh, the Military Housewife back to his family. She initially offered to send it directly to me in Canada; but I decided that it first must go home to 599 Duke Street in Dennistoun, Scotland, from where it had originally left in May 1944. It was important gesture for the housewife to be reunited with the Hugh’s home, the sandstone tenement which has now been in the family for over 110 years, a place which has played host and spectator to five generations of my family who had crossed its threshold.

At the time of my April 2000 trip to

|

| Hugh with his sister Jean in Aberdeen 1940 |

| |

|

|

Hugh at Garelochhead, 20 June

1936 at Scouts and Cubs parents outing |

|

Hugh at Aberdeen 1940 |

|

Hugh with his mother Mary at

Largs 1936 |

The “Field

Service Post Card” shown below was sent by Hugh to his mother. For operational

reasons it has no indication of where it was sent from. The date that Hugh

signed it, 12 September 1944, the 49th Infantry Division were involved in

“Operation Astonia” (10 ~ 12 September 1944), the code name for an Allied

attack on the German-held Channel port of Le Havre in France. It was a combined

British and Canadian operation which resulted in 500 Allied casualties.

The story of about the return of the Post Card (April 2025) can be read at the following blog link, click on the image or the link ….

https://southshoretidewatch.blogspot.com/2025/04/another-piece-from-past-comes-home.html

Below is a postcard, Hugh sent to his mother Mary from Brussels, Belgium, dated 3rd October 1944 ~

WHEN YOU GO HOME

TELL THEM ABOUT US

AND SAY

FOR YOUR TOMORROW

WE GAVE OUR TODAY

|

Hugh’s White Rose of

Yorkshire badges. The 49th (West Riding) Infantry Division was a pre–WWII Territorial Army Division raised in the West Riding of Yorkshire.

Before the later adoption of the Polar Bear formation sign by the Division

whilst in Iceland, the sign was the White Rose of Yorkshire. This was an unusual formation sign in that it was of white

metal with a screw back fitting, other variations exist where the rose has been

painted or has a coloured background. |

|

| Eddie Booth's 49th Infantry (The Polar Bears) Badges and Dog Tags. Similar to Hugh, the 40 is for the Divisional Royal Engineers Headquarters |

|

| Photo of Eddie Booth taken in Belgium during WWII |

|

| Eddie Booth during September 2004 shortly before he died. Note that he is wearing his Polar Bear badges |

|

| Hugh's army Form of Will dated 8 July 1941 |

|

| The War Office ~ Probate Procedure dated 22 February 1945 |

|

| The War Office ~ Certified Notification of Death dated 22 February 1945 |

|

| Officer in Charge of Records, Brighton ~ Personal Effects |

|

| Post Office Savings Department ~ Enumeration of Saving Certificates dated 2 April 1945 |

|

| The War Office ~ Draft of Army Funds due to the Estate dated 14 May 1945 |

|

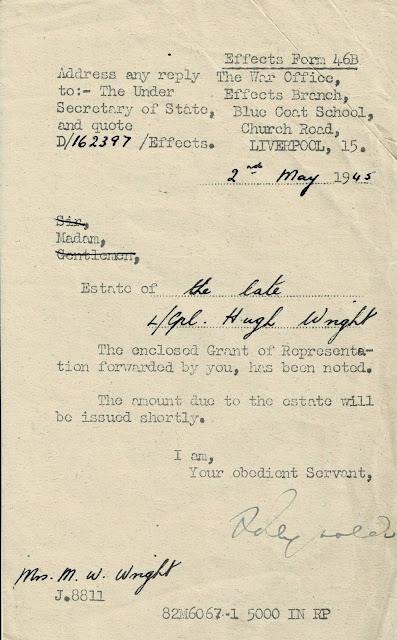

| The War Office ~ Notification of Grant of Representation dated 2 May 1945 |

|

| The Order of Service dated 6 November 1949 for the dedication of the War Memorial |

|

| A letter dated July 2001 from the British Ministry of Defence with Hugh's Record of Military Service |

|

| The Imperial War Graves Commission letter dated 29 October 1946 |

|

| The Imperial War Graves Commission ~ Specimen Drawing of Headstone |

|

| The Imperial War Graves Commission ~ The Care and Marking of War Graves, sent to Hugh's mother Mary |

|

| The Imperial War Graves Commission ~ The Care and Marking of War Graves, sent to Hugh's mother Mary |

|

| The Imperial War Graves Commission ~ The Care and Marking of War Graves, sent to Hugh's mother Mary |

|

| Page from Leopoldsburg |

|

| Grave Registration Report Form |

|

| Grave Concentration Report Form |

|

| Grave Concentration Report Form |

|

| Gravestone Details |

Finally ~

|

Hugh’s last letter to his sister Jean, dated

20 October 1944 the day before he was killed Pages 1 and 2 |

|

Hugh’s last letter to his sister Jean, dated

20 October 1944 the day before he was killed Pages 3 and 4 |

https://southshoretidewatch.blogspot.com/2024/06/euro-2024-my-return-to-leopoldsburg-war.html

Hugh's sister Jean died on June 14th, 2022 at the age of 102 years and 98 days. I wrote the following blog about Jean on November 11th, 2022 ...

https://southshoretidewatch.blogspot.com/2022/11/remembrance-day-2022.html