Omaha Beach …

Historians

concur the landings on the American Omaha Beach, the largest stretch of invasion beach of about 10Km

(6 miles), was the most difficult. Reasons for this, it had the largest number of German troops

defending the area, together with the unfortunate fact that Allied bombs intended to soften up the enemy, fell

off target and largely failed to take out any German strong points. The Germans

made sure the beach was riddled with mines and obstacles. Even mother

nature did not cooperate, stormy weather and navigation issues led to men

drowning, before they could even reach the beach from the British manned Landing

Craft. Those did make it ashore from the U.S. 29th and

1st Infantry Divisions, faced a fortified sea wall and high bluffs from where

German artillery rained down on them. The assault sectors at Omaha were

code-named (from west to east) Charlie, Dog (consisting of Green, White, and

Red sections), Easy (Green and Red sections), and Fox (Green and Red sections).

The battle

on Omaha was so severe that U.S. Lieutenant General Omar Bradley considered a retreat back to England. But slowly and steadily, men clawed through the sand,

then sprinted and ran into enemy fire, making it to the relative safety of the seawall.

The primary

objective at Omaha was to secure a beachhead 8 km (5 miles) deep, between

Port-en-Bessin and the Vire river, linking with the British landings at Gold Beach

to the east, and reaching the area of Isigny to the west to link up with the American

landings at Utah Beach.

From the

beginning everything went wrong at Omaha, German gunners poured deadly fire

into the ranks of the invading Americans. Bodies lay on the beach or floated in

the water. Men sought refuge behind beach obstacles, pondering the deadly

sprint across the beach to the seawall, which offered some safety at the base

of the cliff. Meanwhile, navy destroyers steamed in scraping their bottoms

in the shallow water, blasted the German fortifications at point-blank range. By

nightfall the 1st and 29th Divisions held positions around Vierville,

Saint-Laurent, and Colleville, nowhere near the planned objectives, but they

had a foothold. There were 2400 casualties at Omaha on June 6, but by the end

of the day they had landed 34000 troops.

Omaha Beach 6 June 1944 ~

Pointe du Hoc ...

Formally

part of the Omaha invasion area Pointe du Hoc is a promontory situated to the

west of the landing beach. On D-Day it was the object of a daring seaborne

assault by U.S. Army Rangers, who scaled its cliffs with the aim of silencing

artillery pieces placed on its heights. This ominous piece of land jutting into

the English Channel, provided an elevated vantage point from which huge German

guns with a range of 25 km (15 miles), could deliver fire upon both Omaha Beach

(7 km, or 4 miles, to the east) and Utah Beach (11 km, or 7 miles, to the

west). Allied intelligence and photoreconnaissance had identified five 155-mm

guns emplaced in reinforced-concrete casemates on the Pointe. Allied commanders

had determined that the neutralization of these guns was the key to the fate of

the Omaha and Utah landings. The area of the Pointe was defended by elements of

the German 352nd Infantry Division.

|

| Allied photoreconnaissance showing the position of the German guns |

|

| The resulting Allied D-Day map from the reconnaissance photos of the German guns at Pointe du Hoc |

|

| The Allied D-Day plan for the assault at Pointe du Hoc |

The Ranger

battalions were commanded by Lieutenant Colonel James Earl Rudder. The plan

called for the three companies of Rangers to be landed by sea at the foot of

the 35m (110') cliffs, scale them using ropes, ladders and grapples all while under fire, then engage the enemy at the top of the cliff, all to be carried

out before the main beach landings at Omaha and Utah. The Rangers trained for

the cliff assault on the Isle of Wight under the direction of British

Commandos.

Having

suffered many casualties, when the Rangers made it to the top at Pointe du Hoc,

they were astonished to find the gun bunkers empty, all six guns appeared to have

been recently moved by the Germans. The Rangers regrouped at the top of the

cliffs and a small patrol went off in search of the guns. Two different patrols

found five of the six guns nearby (the sixth was being repaired) and destroyed

their firing mechanisms with thermite grenades.

Pointe du Hoc 6 June 1944 ~

WN65 …

Located at

the bottom of two slopes, the Ruquet Valley was one of the four natural exits

from Omaha Beach that allowed the troops of the 1st American Infantry Division

to escape from the Easy Red beach area. This exit was strongly defended

by a German strong point called WN 65, with its 50mm cannon.

During the

occupation, German forces fortified access to the Ruquet Valley between

Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer and Colleville-sur-Mer. They built a vast

anti-tank ditch that was dug across the width of the valley parallel to the beach, then supplemented with machine gun stations, mortars and a vast set of trenches. After

the beach landings American forces surrounded the bunker, then with the aid of only a halftrack armed with a 37mm cannon, the 50mm barrel gun of WN 65 was

destroyed. In the process 20 Germans were made POWs. The bunker then became the

first headquarters of the Americans on Omaha Beach.

WN65 June 1944 ~

American troops walking past WN 65 with Omaha Beach in the background ~

Les Braves

Memorial Monument (The Monument to the Brave) …

Les Braves

Memorial Monument is located on the sand of Omaha Beach. The monument consists

of three thematic elements: The Wings of Hope, Rise Freedom and The Wings of

Fraternity ….

The Wings of Hope ~

So that the

spirit which carried these men on June 6, 1944 continues to inspire us,

reminding us that together it is always possible to change the future.

Rise

Freedom ~

So that the

example of those who rose against barbarity, helps us remain standing strong

against all forms of inhumanity.

The Wings

of Fraternity ~

So that

this surge of brotherhood always reminds us of our responsibility towards

others as well as ourselves.

The

Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial …

Maintained

by the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC), the Normandy American Cemetery and

Memorial is located at Colleville-sur-Mer. Looking over Omaha Beach it attests

to the American price paid for the liberation in one small corner of France.

Initially established

by the U.S. First Army on 8 June, 1944, at the site of the temporary American

St. Laurent Cemetery, it was the first American cemetery on European soil during

WWII. The cemetery today covers 172.5 acres and contains the graves of 9389 military

dead, most of whom lost their lives during the D-Day landings and ensuing

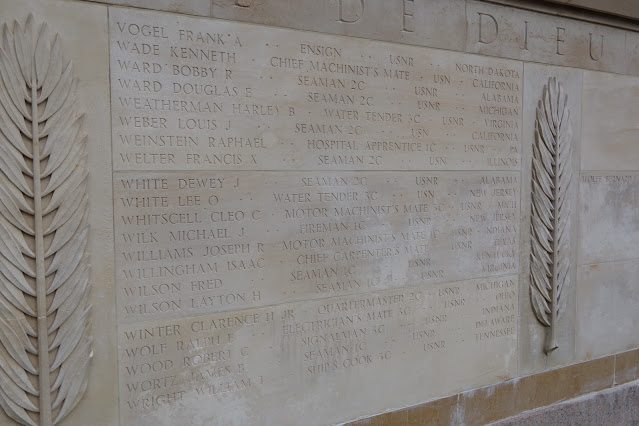

operations. On the Walls of the Missing, are inscribed a further 1557 names

whose graves are unknown, rosettes mark the names of those who have since been recovered or identified.

The

memorial consists of a semicircular colonnade with a loggia at each end, containing large maps and narratives of the military operations. At the center

is the bronze statue, “Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves.” An

orientation table overlooking the beach depicts the landings in Normandy.

Facing west from the memorial in the foreground is the reflecting pool, beyond

is the burial area with its circular chapel, and at the far end are granite

statues representing the United States and France.

Two sons of the 26th President of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt are buried side by side in the cemetery ~ Theodore Roosevelt Jr. killed 12 July 1944, aged 56 (the oldest soldier in the D-Day invasion) and Quentin Roosevelt killed 14 July 1918 (WWI), aged 20. Quentin was originally buried at Chamery, France (about 170Km east of Paris), he was moved to the Normandy location to lie beside his brother in 1955.

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ~

The graves of Robert and Preston Niland ~

There are 45 sets of brothers buried at the Normandy American Cemetery, of which 33 and buried side by side, two of those are Robert and Preston Niland. Along with two more of their serving brothers, the Niland brothers inspired Stephen Spielberg’s film “Saving Private Ryan”.

Following the Sullivan brother’s affair of WWII ~ where all five brothers serving with the US Navy, died together after their light cruiser USS Juneau, was sunk by a Japanese destroyer and submarine on November 13, 1942 ~ US military policy dictated that all attempts should be made, to separate serving brothers into different units or functions of war.

Sergeant

Frederick Niland (April 23, 1920 ~ December 1, 1983) belonged to the 501st

Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 101st Airborne Division.

Technical

Sergeant Robert Niland (February 2, 1919 ~ June 6, 1944) belonged to company D,

505th paratrooper infantry regiment of the 82nd American airborne division.

Lieutenant

Preston Niland (March 6, 1915 ~ June 7, 1944) operated under the command of the

22nd Infantry Regiment of the 4th Infantry Division.

Technical

Sergeant Edward Niland (December 22, 1912 ~ February 28, 1984) was a pilot with

the United States Army Air Force.

Of the

four, Edward and Frederick survived the war, Robert was killed on June 6, 1944 and

Preston the next day on June 7, 1944, both in Normandy.

Due to poor

information following the bomber crash in which Edward was involved on May 16,

1944 (within the Pacific campaign), the American authorities thought that all

but one of the serving brothers had now been killed in action. As a result, Frederick who was also

serving in Normandy was recalled and returned to the USA, where he served in

the Military Police until the war ended in 1945.

As for

Edward, after his B-25 Mitchell was hit, he parachuted and wandered through the

Burmese jungle before being captured. He was held as a Japanese POW in Burma until

being liberated on May 4, 1945.

Their story and that of the Sullivan brother’s and others, inspired the implementation of the 1948 American Sole Survivor Policy.

The following video by the American Battle Monuments Commission has great views of the cemetery and memorial, click on the image or link ~

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M69jhkxhT_I

I was impressed beyond words at the absolute beauty of the American Normandy Cemetery and Memorial. There is nothing the American Battle Monuments Commission could possibly do to make the site any better.

In the same way that I have enormous pride for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission for the work they do, together with their Global reach, I believe every American should be incredibly proud of the American Battle Monuments Commission, for what they have done in Normandy.

These pictures show the cruel life that war brings to the soldiers and the pain and suffering was very evident.

ReplyDelete